.BillMcKibben’s groundbreaking 1989 report on the rise of greenhouse gases and our warming earth.

Nature, we believe, takes forever. It moves with infinite slowness through the many periods of its history, whose names we can dimly recall from high-school biology—the Cambrian, the Devonian, the Triassic, the Cretaceous, the Pleistocene. At least since Darwin, nature writers have taken pains to stress the incomprehensible length of this path. “So slowly, oh, so slowly, have the great changes been brought about,” John Burroughs wrote in 1912.

This, I realize, is a far from novel observation. I repeat it only to make the case I made with regard to time. The world is not as large as we intuitively believe—space can be as short as time. For instance, the average American car driven the average American stance—ten thousand miles—in an average American year releases its own weight in carbon into the atmosphere. Imagine every car on a busy freeway pumping a ton of carbon into the atmosphere, and the sky seems less infinitely blue.

By this I do not mean the end of the world. The rain will still fall, and the sun will still shine. When I say “nature,” I mean a certain set of human ideas about the world and our place in it. But the death of these ideas begins with concrete changes in the reality around us, changes that scientists can measure.

Then, in 1957, two scientists at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, in California, Roger Revelle and Hans Suess, published a paper in the journalon this question of the oceans. What they found may turn out to be the single most important limit in an age of limits. They found that the conventional wisdom was wrong: the upper layer of the oceans, where the air and sea meet and transact their business, would absorb less than half of the excess carbon dioxide produced by man.

And the annual increase seems nearly certain to go higher. The essential facts are demographic and economic, not chemical. The world’s population has more than tripled in this century, and is expected to double, and perhaps triple again, before reaching a plateau in the next century. Moreover, the tripled population has not contented itself with using only three times the resources. In the last hundred years, industrial production has grown fiftyfold.

We have raised the number of termites, too. Like cows, termites harbor methanogenic bacteria, which is why they can digest wood. We tend to think of termites as house-wreckers, but in most of the world they are housebuilders, erecting elaborate, rock-hard mounds twenty or thirty feet high. If a bulldozer razes a mound, worker termites can rebuild it in hours. Like most animals, they seem limited only by the supply of food.

Man is also pumping smaller quantities of other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide, the chlorofluorocarbons—which are notorious for their ability to destroy the planet’s ozone layer—and several more all trap warmth with greater efficiency than carbon dioxide. Methane and the rest of these gases, even though their concentrations are small, will together account for fifty per cent of the projected greenhouse warming. They are as much of a problem as carbon dioxide.

Take Dallas, for instance. According to Hansen’s calculations, the doubled level of gases would increase the annual number of days with temperatures above 100℉. from nineteen to seventy-eight. On sixty-eight days, as opposed to the current four, the nighttime temperature wouldn’t fall below 80℉. A hundred and sixty-two days a year—half the year, essentially—the temperature would top 90℉. New York City would have forty-eight days a year above the ninety-degree mark, up from fifteen at present.

Some recent studies tend to agree with Hansen’s conclusion that the warming has already begun: precipitation appears to have increased above 35 degrees north latitude and decreased below it since the early nineteen-fifties, for instance—a result anticipated in the greenhouse models. And some investigators have found a “variable but widespread” warming of the Alaskan permafrost, which changes temperature much more slowly than the air and thus may provide a better record.

There is debate, though, over the question of what will happen as the heating begins. A large-scale change in the climate will set off a series of other changes, and while some of these would make the problem worse, others might lessen it. Skeptics are inclined to argue that the warming will trigger some natural compensatory brake. S.

But the trees that live here don’t do so because of the laws; they do so because of the climate. They have slowly marched north as the climate warmed since the end of the last ice age, and if it continued slowly warming they would slowly keep marching; the convoy of pines might march right out of here, and the mass of hardwoods found in lower Appalachian latitudes might march in to replace them.

Most mornings, I hike up the hill outside my back door. Within a hundred yards, the woods swallow me up, and there is nothing to remind me of human society—no trash, no stumps, no fences, not even a real path. Looking out from the high places, you can’t see road or house; it is a world apart from man. But once in a while someone will be cutting wood farther down the valley, and the snarl of a chain saw will fill the woods.

Of a thousand examples, my favorite single description comes from George Catlin, who travelled the frontier in the eighteen-thirties to paint the portraits of American Indians. In his journal he describes a valley, “far more beautiful than could have beenby mortal man,” in which he spent the night on a ride north from Fort Gibson to the Missouri River:

We discovered that Clear River emerged from none of the three gorges we had imagined, but from a hidden valley which turned almost at right angles to the east. I cannot convey in words my feeling in finding this broad valley lying there, just as fresh and untrammelled as at the dawn of geological eras hundreds of millions of years ago. Nor is there any adequate way of describing the scenery. . . .

But now the basis of that faith is lost. The idea of nature will not survive the new, global pollution—the carbon dioxide and the methane and the like. This new rupture with nature is different both in scope and in kind from salmon tins in an English stream. We have deprived nature of its independence, and that is fatal to its meaning.

It is also true that this is not the first huge rupture in the globe’s history. Some thirty times since the earth formed, “planetesimals” at least ten miles in diameter and travelling at sixty times the speed of sound have crashed into the earth, releasing perhaps a thousand times as much energy as would be liberated by the explosion of all present stocks of nuclear weapons; such events, some scientists say, may have destroyed up to ninety per cent of all living organisms.

Scientists may argue that natural processes still rule, that the chemicals even now trapping the earth’s reflected heat or eating away the ozone or acidifying the rain are proof that nature is still in charge—still our master. Some have talked about God as present in the interstices of the atom, or in the mysteries of quantum theory, or in the double helix of DNA and other bits of “information.

Other proposals are even odder. The Columbia geochemist Wallace Broecker has speculated about the use of “a fleet of several hundred jumbo jets” to ferry thirty-five million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere annually, in order to reflect sunlight away from the earth. Other scientists recommend launching “giant orbiting satellites made of thin films,” which could cast shadows on the earth, counteracting the greenhouse effect with a sort of venetian-blind effect.

Some dim recognition that God and nature are intertwined has led us to pay at least lip service to the idea of “stewardship” of the land. If there is a God, He probably does want us to take good care of the planet, but He may want something even more radical. The Old Testament contains in the book of Job one of the most far-reaching defenses ever written of wilderness—of nature free from the hand of man. The argument gets at the heart of what the loss of nature will mean to us.

With this new power comes a deep sadness. I took a day’s hike last fall, following the creek that runs by my door to the place where it crosses the main county road. It’s a distance of maybe nine miles as the car flies, but rivers are far less efficient, and endlessly follow time-wasting, uneconomical meanders. The creek cuts some fancy figures, and so I was able to feel a bit exploratory—a budget Bob Marshall. In a strict sense, it wasn’t much of an adventure.

Our local shopping mall has a club of people who go “mall-walking” every day. They circle the shopping center en masse—Caldor to Sears to J. C. Penney, circuit after circuit, with an occasional break to shop. This seems less absurd to me now than it did at first. I like to walk in the outdoors not solely because the air is cleaner but also because outdoors we venture into a sphere larger than we are.

It is this very predictability that has allowed most of us in the Western world to forget about nature, or to assign it a new role, as a place for withdrawing from the cares of the human world. In some parts of the globe, nature has been more capricious, withholding the rain one year or two, pouring it down by the lakeful the next, and in those places people think about the weather—about nature—more than the rest of us do.

But the salvation of the West Antarctic does not mean the salvation of Bangladesh, or even of East Hampton. A number of other factors may raise sea level significantly. Glaciers bordering the Gulf of Alaska, for example, have been melting for decades, and constitute a source of fresh water about the size of the entire Mississippi River system. And even if nothing at all melted, the increased heat would raise sea level considerably.

Should the ocean go up a metre, at least half the nation’s coastal wetlands will be lost one way or another. “Most of today’s wetland shorelines still would have wetlands,” according to the E.P.A. report to Congress. “The strip would simply be narrower. By contrast, protecting all mainland areas would generally replace natural shorelines with bulkheads and levees.

And matters may get worse.

Argentina Últimas Noticias, Argentina Titulares

Similar News:También puedes leer noticias similares a ésta que hemos recopilado de otras fuentes de noticias.

Increased Memory B Cell Potency and Breadth After a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Boost - NatureNature - Increased Memory B Cell Potency and Breadth After a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Boost

Leer más »

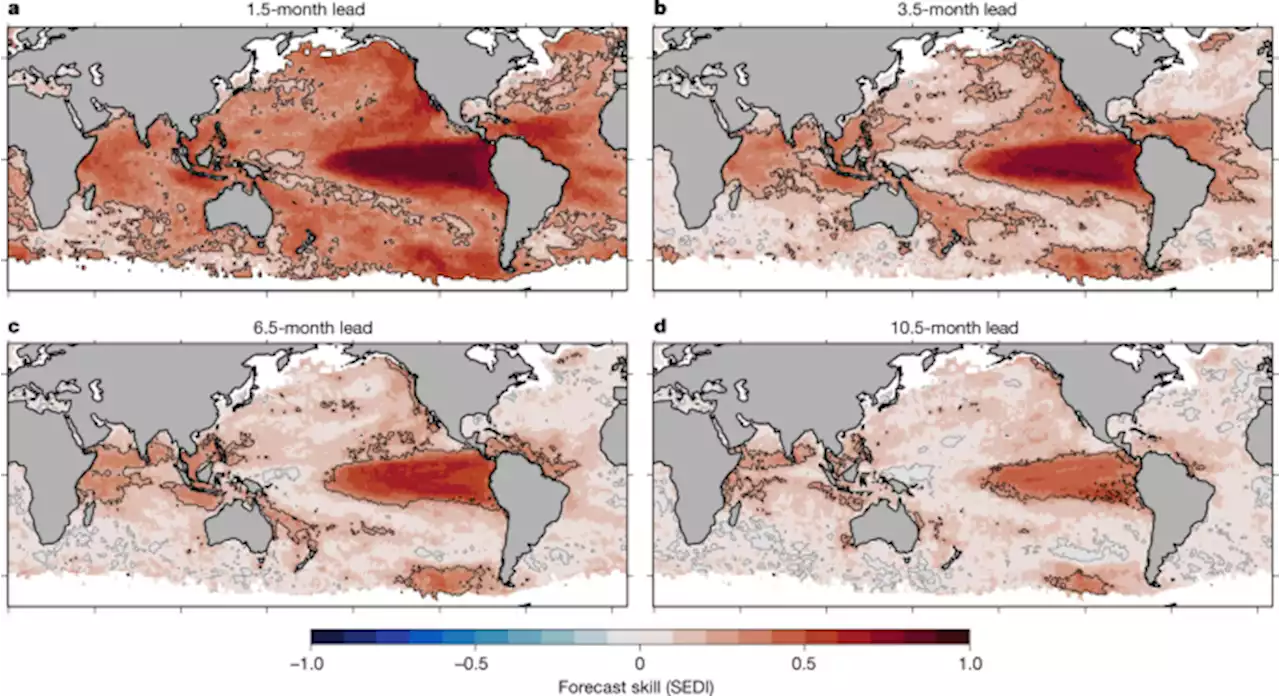

Global seasonal forecasts of marine heatwaves - NatureClimate forecast systems are used to develop and evaluate global predictions of marine heatwaves (MHWs), highlighting the feasibility of predicting MHWs and providing a foundation for operational MHW forecasts to support climate adaptation and resilience.

Global seasonal forecasts of marine heatwaves - NatureClimate forecast systems are used to develop and evaluate global predictions of marine heatwaves (MHWs), highlighting the feasibility of predicting MHWs and providing a foundation for operational MHW forecasts to support climate adaptation and resilience.

Leer más »

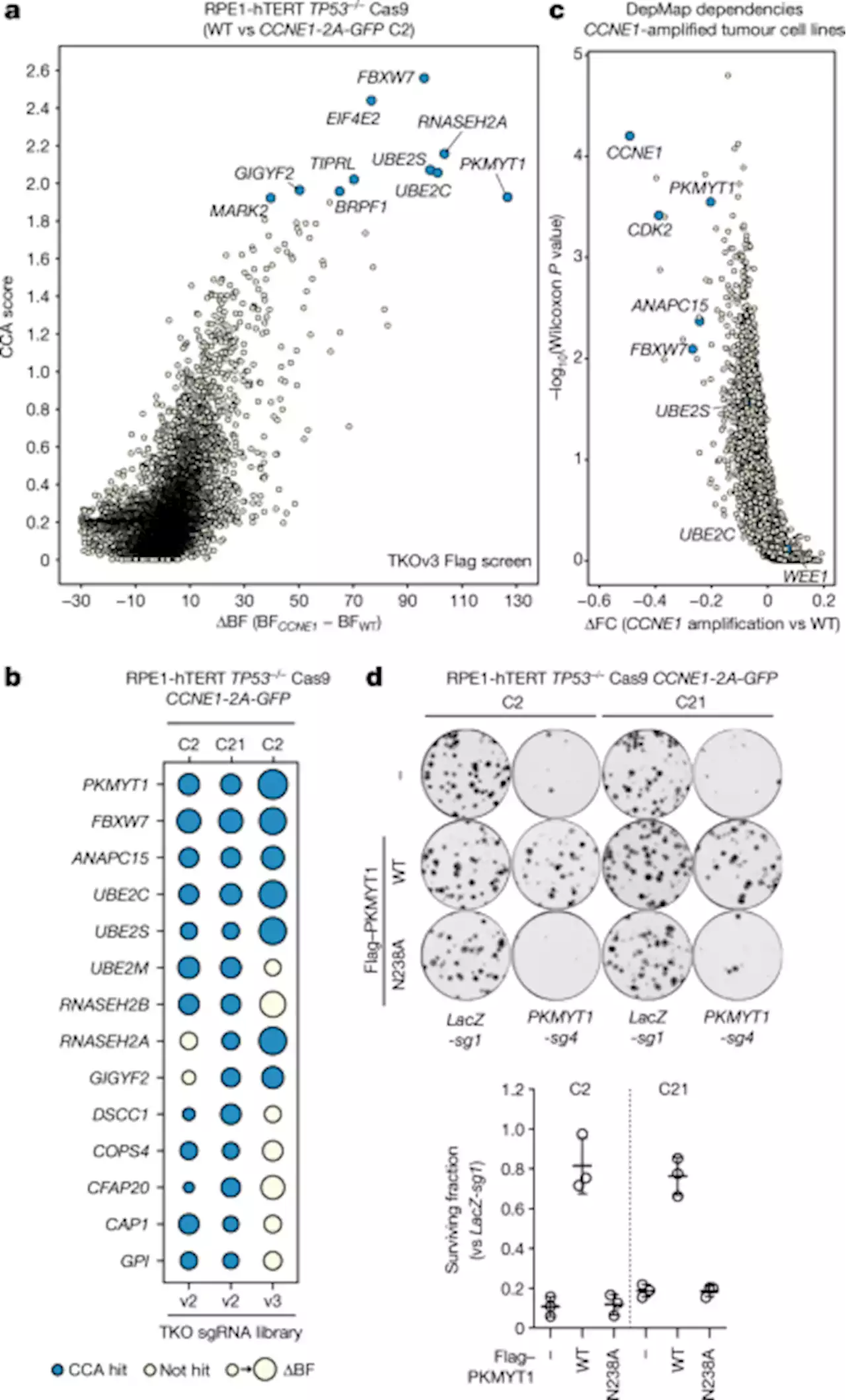

CCNE1 amplification is synthetic lethal with PKMYT1 kinase inhibition - NatureGenome-scale CRISPR–Cas9-based synthetic lethality screens identify PKMYT1 as a potential therapeutic target in tumours with CCNE1 amplification.

CCNE1 amplification is synthetic lethal with PKMYT1 kinase inhibition - NatureGenome-scale CRISPR–Cas9-based synthetic lethality screens identify PKMYT1 as a potential therapeutic target in tumours with CCNE1 amplification.

Leer más »

Intron-mediated induction of phenotypic heterogeneity - NatureExperiments in yeast show that introns have a role in inducing phenotypic heterogeneity and that intron-mediated regulation of ribosomal proteins confers a fitness advantage by enabling yeast populations to diversify under nutrient-scarce conditions.

Intron-mediated induction of phenotypic heterogeneity - NatureExperiments in yeast show that introns have a role in inducing phenotypic heterogeneity and that intron-mediated regulation of ribosomal proteins confers a fitness advantage by enabling yeast populations to diversify under nutrient-scarce conditions.

Leer más »

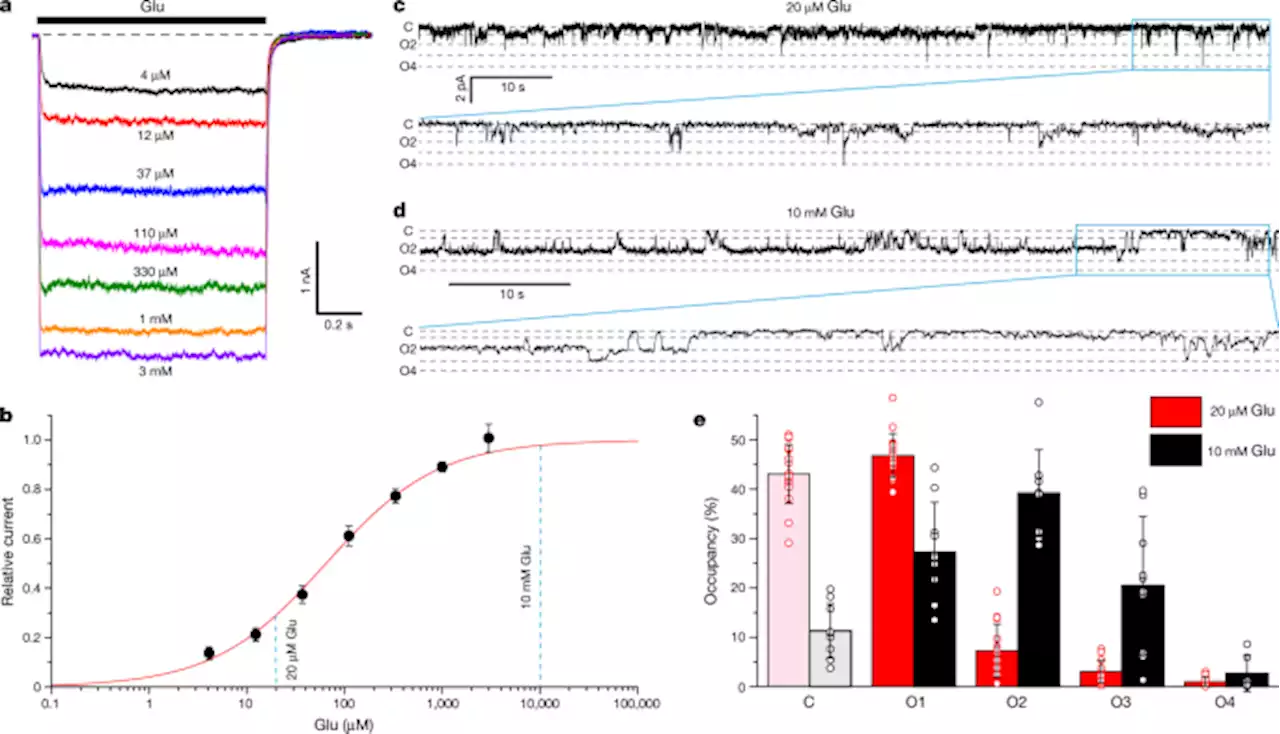

Opening of glutamate receptor channel to subconductance levels - NatureCryo-EM structures of AMPA receptor with the subunit γ2 in non-desensitizing conditions at low glutamate concentrations disprove the one-to-one link between the number of glutamate-bound subunits and ionotropic glutamate receptor conductance.

Opening of glutamate receptor channel to subconductance levels - NatureCryo-EM structures of AMPA receptor with the subunit γ2 in non-desensitizing conditions at low glutamate concentrations disprove the one-to-one link between the number of glutamate-bound subunits and ionotropic glutamate receptor conductance.

Leer más »