According to some estimates, more than 60 per cent of people with Alzheimer’s disease will wander away from home or a caregiver, laying bare a painful truth about life with dementia: risk and freedom are inextricably intertwined.

Nancy Paulikas and her husband, Kirk Moody, arrived at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on October 15, 2016. Museumgoing had been among the couple’s many hobbies in retirement, along with travel, hiking, and gardening. But, since Paulikas’s diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s, the year before, it had become hard to say how an outing might go.

While her family searched, an office-tower security camera captured images of Paulikas striding purposefully westward on Wilshire Boulevard, pausing only at crosswalks. Less than an hour after Moody last saw her, another camera recorded a grainy image of Paulikas walking southwest down the busy thoroughfare of McCarthy Vista, her eyes ahead and her steady pace unchanged.

Years can pass between the toppling of the first neurological domino and the onset of the short-term memory problems that typically prompt worried patients or their families to seek medical advice. Karen Duff, the director of the Dementia Research Institute at University College London, told me that an Alzheimer’s-afflicted brain wasn’t unlike a buggy G.P.S. device that, with increasing frequency, blanks out parts of the map.

In 1992, Robert Koester, a specialist in lost-person behavior, published a research paper analyzing the stories of twenty-five missing persons with dementia. The project morphed into what is now the International Search & Rescue Incident Database—a collection of more than two hundred and fifty thousand case files describing missing persons of all kinds.

Wandering is most frequent in the middle stages of Alzheimer’s, when the disease has progressed far enough to disrupt an individual’s cognitive functions but not enough to impair their motor skills. Many patients report depression, restlessness, and anxiety during this time, both as a direct consequence of the changes in their brains and as an understandable response to the frustrations of navigating life without the aid of consistent memory. But there can be good days as well.

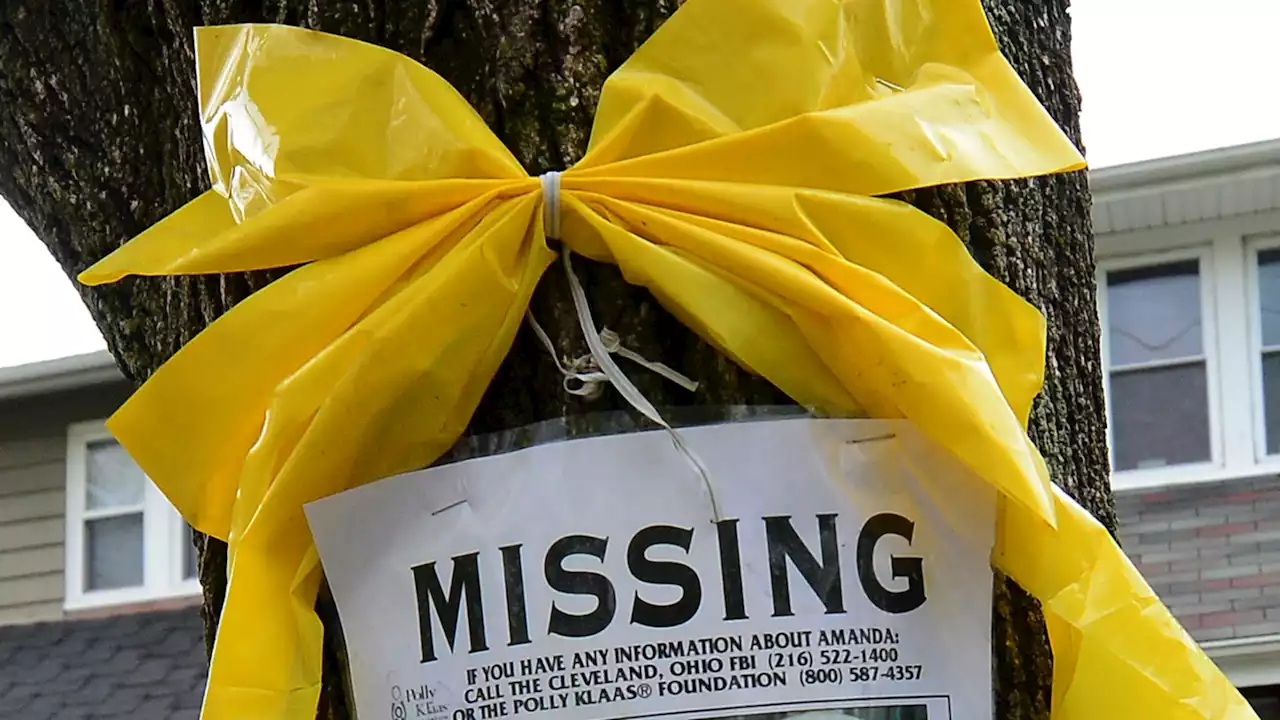

The majority of U.S. states have notification systems, sometimes called Silver Alert programs, that activate when a vulnerable senior goes missing. Even when these alerts reach the public, however, there isn’t widespread understanding of how best to engage with a person who has dementia.

Argentina Últimas Noticias, Argentina Titulares

Similar News:También puedes leer noticias similares a ésta que hemos recopilado de otras fuentes de noticias.

One person dead, search called off for 4 missing from Southeast fishing charter boatThe U.S. Coast Guard has recovered the body of one person and has called off the search for four more people from a fishing charter vessel that was last seen near Sitka on Sunday afternoon.

One person dead, search called off for 4 missing from Southeast fishing charter boatThe U.S. Coast Guard has recovered the body of one person and has called off the search for four more people from a fishing charter vessel that was last seen near Sitka on Sunday afternoon.

Leer más »

K-9 helps find missing therapy dog in Rhode Island woodsA beloved beagle -- and former high school therapy dog -- is now back with his owner after spending days lost in the woods.

K-9 helps find missing therapy dog in Rhode Island woodsA beloved beagle -- and former high school therapy dog -- is now back with his owner after spending days lost in the woods.

Leer más »

'Ebony Alert': CA bill aims to create notification system to help find missing Black youth, womenIf passed, the bill would establish an Ebony Alert to address the lack of attention to Black youth and young Black women that go missing in California.

'Ebony Alert': CA bill aims to create notification system to help find missing Black youth, womenIf passed, the bill would establish an Ebony Alert to address the lack of attention to Black youth and young Black women that go missing in California.

Leer más »

How to find out if your child is attending school and other Philadelphia attendance resourcesThe School District of Philadelphia has several online resources for parents, guardians, and students struggling to get to school regularly.

How to find out if your child is attending school and other Philadelphia attendance resourcesThe School District of Philadelphia has several online resources for parents, guardians, and students struggling to get to school regularly.

Leer más »

Find Satoshi Labs Rolls Out AI Tool That Turns Selfies Into NFTsThe parent company behind Web3 game STEPN is releasing GNT V3, which will allow users to turn their selfies into digital artworks on the Solana blockchain.

Find Satoshi Labs Rolls Out AI Tool That Turns Selfies Into NFTsThe parent company behind Web3 game STEPN is releasing GNT V3, which will allow users to turn their selfies into digital artworks on the Solana blockchain.

Leer más »